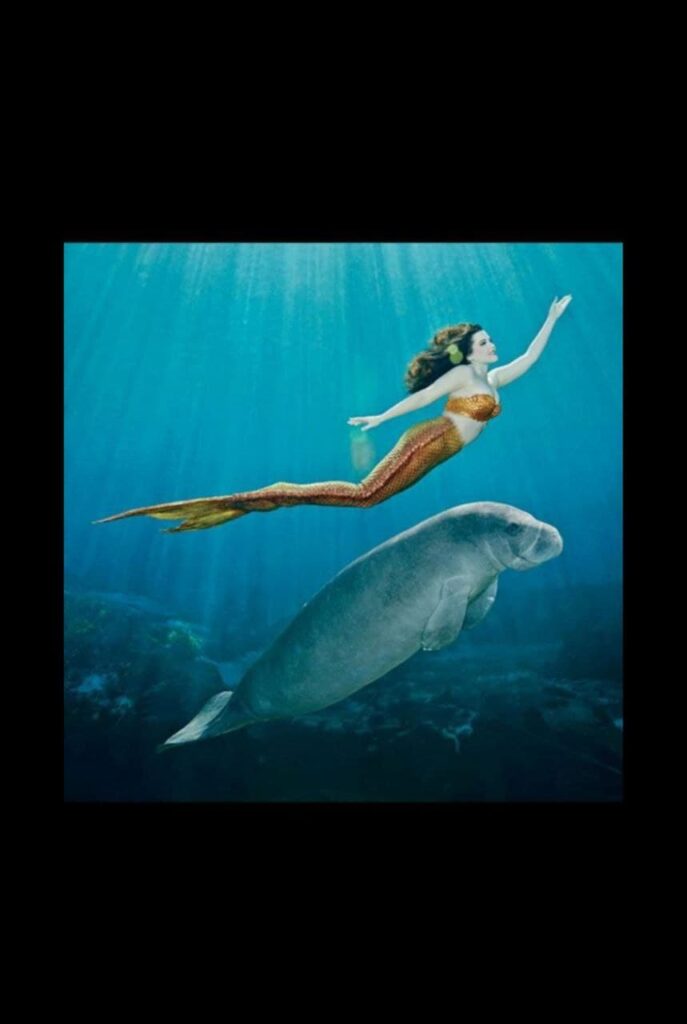

Mermaids are probably the most fantasized beings in human imagination. Part fish-part women mythological beings, the mermaids are lost somewhere in the folklores today. On the brink of vanishing into the folklores are the creatures (Dugongs) who happen to be their nearest living resemblance and the muse behind the folk tales.

The Voices explores the ecological significance of the species and roads to India’s first Dugong conservation park recently announced by Tamil Nadu Government.

Dugongs

Also known as “sea cows,” Dugongs graze on sea grasses in shallow coastal waters of the Indian and western Pacific Oceans. Dugongs are cousins of manatees and share a similar plump appearance, but have a dolphin fluke-like tail. But unlike manatees, which reside in freshwaters, Dugong strictly inhabit marine ecosystems.

Why Dugongs are critical to Marine ecosystem?

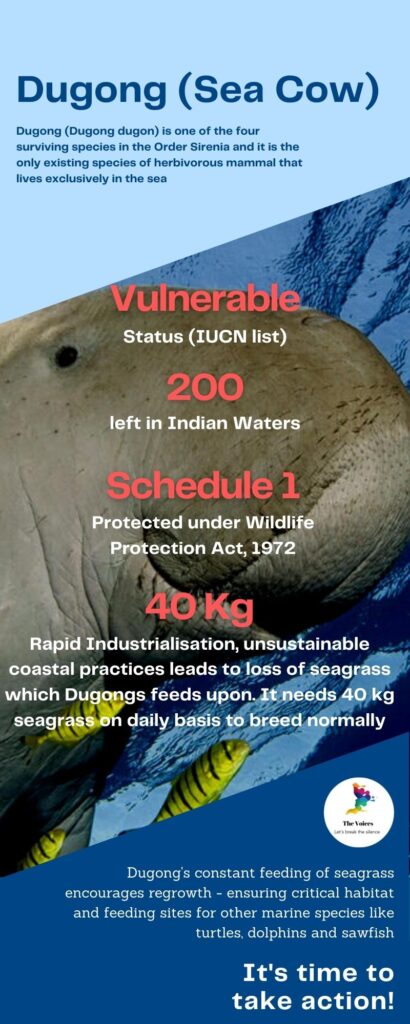

Dugongs are consumers of seagrass. They consume 40kg of seagrass daily and help in the regrowth of fresh vegetation. As per World Wildlife Fund for Nature “Wherever they survive, dugongs play an important role in maintaining coastal ecosystems. Their constant browsing of seagrass encourages regrowth – ensuring critical habitat and feeding sites for a host of other marine species, including turtles, dolphins and sawfish.”

Why seagrass ecosystem assumes importance?

Dugongs ensure healthy regeneration of seagrass ecosystem. Seagrass ecosystems are as vital as coral reef systems because they are critical to the success of coastal fisheries. Seagrass also play an important role in reducing the effects of climate change. Healthy growth of seagrass fulfills dietary needs of coastal communities and millions of consumers of fish and seafood globally. They also protect coasts from the impacts of storms, improve the quality of marine water. Hence Dugong conservation is being called for globally.

Why are Dugongs vulnerable to extinction?

Despite being able to travel long distances, Dugong populations are considered to be declining across world. It is estimated that populations have suffered a global decline of approximately 20% over the last century, largely due to human activities.

Human activities such as the destruction and modification of habitat, pollution, rampant illegal fishing activities, vessel strikes, unsustainable hunting or poaching and unplanned tourism are the main threats to Dugongs.

A few biological characteristics of Dugongs – long-life span, with low reproductive rates, long generation times and a high investment in each offspring – make their conservation problematic when the world is already up against a range of human threats.

The loss of seagrass beds due to ocean floor trawling (trawling along sea floor) is another important factor behind contracting Dugong populations in many parts of the world.

Exhaustive and sustainable conservation is the only way to save Dugongs from extinction. Conservation in places like Australia has seen their population crossing 85,000. Experts believe the use of the wisdom of indigenous coastal communities too holds a key to the success of such conservation plans.

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies Dugongs or Sea Cow as a vulnerable species. The existential threat has inspired a spectrum of conservation measures. The latest in the fray is the Tamil Nadu Government’s announcement of India’s first Dugong Conservation Reserve in Palk Bay.

On Friday, September 3rd 2021, Tamil Nadu Government announced the plans to set up the reserve in the southeastern coast of the state.

Confirming the same in a social media post, Tamil Nadu’s Environment Secretary – Supriya Sahu, said, “Government of Tamil Nadu will set up India’s first Dugong Conservation Reserve in the Palk Bay. Dugong or the sea cow is an endangered marine species & survives on seagrass that is found in the area. The conserve will cover an area of 500 Km.”

K Ramachandran, Minister of Forests, TN Government further added that the project will be established through sustained community participation.

‘Counting’ the crisis in India

Interestingly, though only one species of Dugong survives in Indian marine waters today, an IIT Roorkee research headed by Dr. Sunil Bajpai confirmed that an astonishing diversity of Dugongs existed in pre historic (about 42 million years ago) Indian waters.

According to a 2013 Zoological survey of India (ZSI) survey there were just 250 Dugongs in the Gulf of Mannar in Tamil Nadu, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Gulf of Kutch in Gujarat. In light of the worrying numbers and frequent reports of their hunting, the recently announced measure assumes substantial value.

Road to Reserve

In 2019, the Wildlife Institute of India recommended Tamil Nadu Forest Department to declare the 400 sq km stretch of Palk Bay as a Conservation Reserve for Dugongs.

In July 2020, K Pushpavanam, a law student and nature enthusiast from Madurai filed a petition in Madras High Court to seek judicial intervention for enforcement of the recommendations.

Apart from this Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun (Uttarakhand) has constructively engaged communities to indulge in conservation practices for Dugongs and quit their consumption as meat.

K Sivakumar, a senior scientist of the department of Endangered Species Management at the WII, in an interview to Down to Earth, confirmed that a decade back, fishermen used to sell dugong meat at Rs 1,000 per kg in Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Andaman and many consumed the meat under the wrong impression that it would cool their body temperature.

In February 2020, at Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India also hosted the 13th Conference of parties (CoP) of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), an environmental treaty under the aegis of the United Nations Environment Programme.

Sivakumar says, “The Government of India is a signatory to the CMS since 1983. India has signed non-legally binding Memorandums of Understanding with CMS on the conservation and management of Siberian Cranes (1998), Marine Turtles (2007), Dugongs (2008) and Raptors (2016).”

The recent move of establishing a dedicated reserve happens to be a major leap in living the conservation commitment for Dugongs. Whatever the means may be, the end is an indispensable one, as reviving Dugongs is about reviving a critical niche of marine ecosystem.

Edited by Raghujit S. Randhawa