Among all the theories and conclusions that the Haryana election results have led to, what stood out prominently was the discourse over the relevance of the anti-defection law in India. The act, originally meant to curb political defection cases, has been controversial ever since it was passed. While those who back the act contend that it is essential for maintaining political stability, sceptics assert that it impedes the democratic process.

A cross-section of judiciary experts, political thinkers, and journalists who spoke to The Voices had some interesting observations on the issue.

Why the law was needed?

Author GC Malhotra in his book published Anti-Defection Law in India and the Commonwealth, published by Lok Sabha Secretariat, stated India started to witness widespread political defections by lawmakers in the late 1960s, which crippled governments.

He noted that the Indian political landscape experienced a notable trend of legislators switching political parties for reasons beyond ideological differences.

In the sixties, changing political parties for reasons other than ideological engulfed the Indian polity scenario. Out of roughly 542 cases in the entire two-decade period between the first and the fourth general elections, at least 438 defections occurred in these 12 months alone. Among independents, 157 out of 376 elected joined various parties in this period. That lure of office played a dominant part in the decisions of legislators to defect was obvious from the fact that out of 210 defecting legislators of various states, 116 were included in the councils of ministers, which they helped to form by defections.

Justice S. Ranjit Singh Randhawa (Retd), Judge of Punjab and Haryana High Court recalled the notable incident in Haryana in 1967 about politician Gaya Lal, who changed his party three times in a single day, leading to the coining of one of the most popular Hindi quotes mocking defectors: Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram. Frequent party defections led to a tumultuous political environment, affecting governance. The main intent of the law was to combat ‘the evil of political defections.’

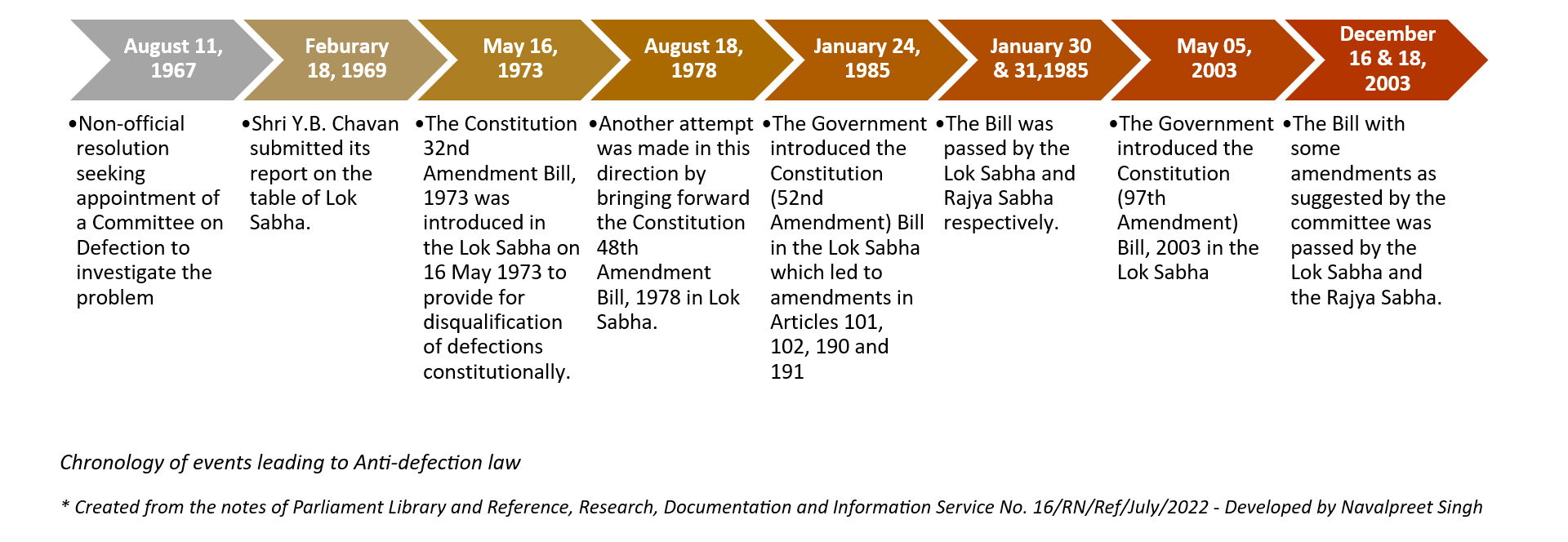

How did the law come into being?

Justice R.S. Randhawa said that while the law was floated with the intention of stopping the party-hopping culture in politics, it has failed to achieve its intended purpose. It has rather led to party-hopping without any moral compunction.

The then PM Rajiv Gandhi proposed this bill. Both houses unanimously approved it, and it came into effect on 18 March 1985 after getting the assent of the President. The tenth Schedule of the Constitution added this law through the 52nd Amendment in 1985. The Anti-Defection Law aims to ensure that political members do not betray the trust of their constituents by switching parties without a valid reason and to maintain the stabilization of the party. Be it a Member of Parliament (MP) or a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), who defects from his or her party to join another, faces the risk of disqualification. It is designed to keep the elected representatives loyal to the people who elected them into power by casting their votes rather than yielding to the lure of political opportunism.

91st amendment made to the Anti-Defection Law in 2003?

In 2003, then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee introduced the 91st amendment to the law. The government removed major loopholes in the law that the politicians were exploiting. It changed the law from one-third to two-thirds of members from a political party.

Dr. Jagrup Singh Sekhon, Retd. Professor of Political Science at Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, said that this amendment enhanced the integrity of India’s parliamentary democracy. It emphasized the need for stability in governance by curbing opportunistic defections, which often led to the destabilization of elected governments.

Anti-Defection beyond Indian borders

Many nations have implemented laws to dissuade defectors, ensure loyalty, and preserve efficient governance. These include countries like Singapore, Nepal, Pakistan, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa. The Singapore Constitution states that a member of parliament loses his/her place in parliament if expelled, resigned, or barred from the political party from which he/she was elected.

Professor (Dr.) Deepak Kumar Chauhan, Dept. of Law, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, said India’s Anti-Defection Act of 1985 sought to mitigate party-switching and promote political stability. Conversely, democracies like the UK depended on internal party discipline without legal restrictions. Countries like South Africa possessed adaptable anti-defection laws that reconcile party allegiance with individual autonomy. India’s legislation is more stringent yet is criticised for suppressing dissent, while more sophisticated models facilitate increased discourse inside party systems.

Is giving tickets to party loyalists key to avert defection?

Doctor-turned-politician Dr. Inderbir Singh Nijjar, MLA and Ex-Cabinet Minister for Local Government in Punjab, said that political parties, too, should do some introspection. He suggests that giving tickets only to party loyalists is a key strategy to avert defection. Parties should show the door to the turncoats. Also, putting the onus on the candidates, he added that the candidates should remain loyal to their voters and party throughout their five-year term.

The power of the Chairman or Speaker in deciding the disqualification cases

The Chairman or Speaker of the respective legislative house is the ultimate decision-making authority in disqualification cases. The law does not define a period in which disqualification proceedings against a legislator should be decided. With the role of the Speaker of the House becoming increasingly political, disqualifications are either decided immediately or kept pending indefinitely, depending on what suits the political party the Speaker was previously affiliated with. Commenting on it, Amit Sharma, Resident Editor Dainik Jagran, said that in the present scenario, the Speaker is the one who cannot speak even if he or she disagrees or has an opinion in contrast to the line being towed by the ruling party. Adding to it, Dr. Sekhon said speakers of legislative bodies, though intended to be neutral arbiters, often showed an inclination towards their own parties and candidates. While the authority to make crucial decisions is vested in the Speaker, including those related to defections under the anti-defection law, he adds that impartiality remains elusive.

Theoretically, the Speaker should serve as a guardian of fairness, representing the interests of all parties. However, in practice, this ideal is far from being realized, as partisan loyalties frequently influence decisions. Amit Sharma adds that the true essence of this law, which aims to uphold neutrality, remains a distant dream.

Should an independent tribunal be set up to decide anti-defection cases?

The law proposed that the Election Commission be the deciding authority in defection cases. At the same time, the Supreme Court suggested that Parliament establish an independent tribunal headed by a retired judge of the higher judiciary to decide defection cases swiftly and impartially. However, Justice R.S. Randhawa added that to avoid defection, the amendment was needed to a provision that led to the automatic disqualification of an elected member who changed his/her party on whose symbol he/she was elected. He/she should be ineligible to contest elections or hold any ministerial post or any other post for six years so that he/she cannot participate in at least two elections. He advocated the need to create an independent tribunal to deal with the issue of defection.

What kind of reforms can be introduced?

Professor (Dr.) Chauhan said that to fortify democracy, reforms must include increased transparency in party financing, enhanced internal party democracy and clearer regulations on anti-defection measures. Limiting unchecked executive power and boosting judicial oversight could mitigate the misuse of defection laws. He proposes promoting greater accountability, grassroots engagement, and improved public discourse is key to restoring voter confidence.

Copyedited by: Nelson Mudaliar