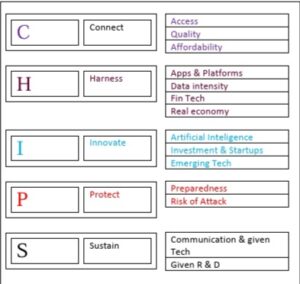

The CHIPS (Connect, Harness, Innovate, Protect, and Sustenance) framework, from the State of India’s Digital Economy (SIDE) Report 2025 by the ICRIER-Prosus Centre for Internet and Digital Economy (IPCIDE), has highlighted the digital paradox that the country is reeling under. While the country’s overall digital growth appears impressive, the average Indian’s access to and participation in the digital era remain very limited.

The Voices student reporter unravels the report in the backdrop of the transformative impact that digital technology has on citizens. The student contacted the World Bank to seek more information on the subject and deciphered the figures accordingly.

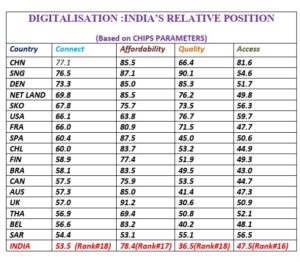

India ranks as the third-largest digitalised country in the world, just behind China and the US. India’s rank, however, falls to 28th position on the relative scale, i.e., CHIPS (a parameter based on users’ Connectivity, Harness, Innovation, Protection, and Sustenance). This means while India as a country has achieved a high level of digitalisation at the aggregate level, the level of digitalisation for the average Indian remains fairly modest.

With respect to connectivity, affordability, quality, and accessibility in digitalisation, India ranks 18th, 17th, 18th, and 16th, respectively. This means that while many Indians use smartphones and the internet, a significant number remain unconnected or lack access to quality digital services.

Digitalisation or digital inclusion significantly impacts citizens’ daily lives and areas. It includes various institutions and individuals who are stakeholders and play a crucial role in bringing meaningful change to the country’s digital landscape. These institutions are fueling India’s digital transformation and contributing to the country’s digital economy by facilitating initiatives such as Digital India, Aadhaar, financial inclusion, and e-governance.

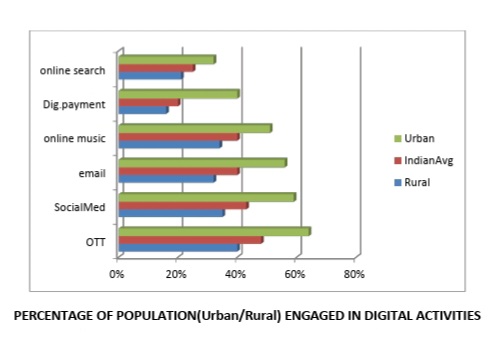

Digital exclusion or non-inclusion can have negative impacts, especially for vulnerable populations, which eventually gives rise to an acute digital divide. The factors contributing to the digital divide include a lack of digital literacy, the existing gender gap, socio-economic factors such as income, education, and occupation, and rural-urban disparity.

The CHIPS – Mobile Boom, Limited Inclusion, Gender Gaps

According to the report, the connect pillar remains India’s Achilles’ heel, ranking 18th among 32 countries in the sample. A stark contrast, India’s second-largest network of internet and smartphone users globally coexists with over 40 per cent of non-users of the internet and over 50 per cent without smartphones.

The level of digitalisation for the average Indian remains fairly modest. The only four sample countries that perform worse than India are Egypt, Indonesia, Nigeria and South Africa. Scores in the CHIPS Economy are driven much more by the population and overall size of the economy (GDP) than by per capita income. Chronologically, the US, China, and India outshine all other countries in absolute score. The elevated scores of India are likely to be driven by its large population, while those of the US are driven by its large economy. In the case of China, it has an advantage in both.

The imbalance between mobile and broadband networks seems unusually high. India is the only country, other than Nigeria (in the sample), where the traffic flow on mobile networks exceeds that on fixed networks. The ratio of fixed broadband to mobile network is 1:0.2 in the United States, 1:0.6 in China and 1:2 in India.

While a mobile-first network has helped accelerate the adoption of the internet in India, the lack of a complementary fibre backbone risks resiliency and can adversely affect the country’s digital ambition. Analysis using state-level data finds that the likelihood of a male internet user also using digital payments is higher than that for a female internet user.

UPI Boosts Inclusion, But Women and Rural India Lag

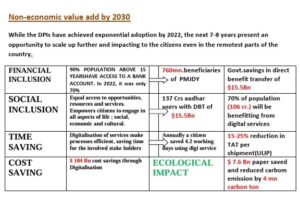

In India, UPI helped to accelerate financial inclusion as legacy systems were slow to transform. India can leverage the explosive growth in digital payments to strengthen its financial technology-based ecosystem, while ensuring suitable guardrails to protect consumers. By 2030, access to bank accounts is expected to increase to 90%, Aadhaar users will reach 137 Crores, 70% of the population will benefit from digital services, 4.2 average working days will be saved per citizen annually through digital services, and carbon emissions will be reduced by 4 million tons of carbon.

India’s innovation capabilities are greater than its level of development, but nowhere near that of a leading nation, states the report on India’s Digital Economy, published by the Centre for \Internet and Digital Economy.

In rural India, access to the internet remains a significant barrier for women to utilise digital payments, and a greater proportion of those gaining access to the internet are individuals, such as the youth, who are likely to make more diverse and bolder use of the internet.

In rural India, access to the internet remains a significant barrier for women to utilise digital payments, and a greater proportion of those gaining access to the internet are individuals, such as the youth, who are likely to make more diverse and bolder use of the internet.

Kerala – The 100% Digital State

In contrast to the report by the Centre for Internet and Digital Economy, Kerala achieved 100% digital literacy. With technology redefining literacy to include digital competence, the state launched the Digi Kerala project. The project aimed at enabling all citizens to use online services, particularly those provided through the K-SMART platform in local bodies.

Likewise, the inference apparently drawn in the above report seems not to be convincing, at least as far as Indian efforts to bridge the digital divide are concerned. The World Bank has taken initiatives as a facilitator in various projects, such as GYANDOOT in the Dhar district of Madhya Pradesh, to bridge the existing digital divide in rural India. In response to a query on this issue sent by The Voices via email to the World Bank, it replied with several research paper links, including one referring to a paper published by NASSCOM and Arthur D. Little.

A Journey From Digital Divide to Digital Dividends

The report of NASSCOM and Arthur D. Little titled “Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) of India Accelerating India’s Digital Inclusion (sent by the World Bank to The Voices) emphasises the importance of DPI in driving economic growth. It states that by 2030, India will gallop towards a robust digital economy, riding on a robust DPI, aiming for a $1 trillion digital economy.

According to the report, by 2030, the economic value added from DPIs is expected to increase by ~3 times, from the current 0.9% to 2.9-4.2%, driven by existing digital entities that will evolve to deliver a superior user experience, utilising new-age technologies such as AI, Web 3, and others. Aadhaar is expected to continue being a major contributor as use cases expand to a broader range of services.

Enhanced impact of budding DPIs such as Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission. (ABDM) (better healthcare for citizens of the country, resulting in increased labour productivity) and ONDC (incremental growth in retail spending of the country).

Key imperatives to be cognizant of include proactive policy support and regulatory clarity, as well as the promotion of the use of existing digital networks for both the government and the private sector. MSMEs and Startups need to adopt existing digital infrastructure.

DPIs can revolutionise the entire Indian economy with inclusive growth, bringing down the digital divide to a minimum. An optimistic picture can now be painted, drawing inspiration from Kerala, of an interconnected, open, and inclusive world with infinite possibilities for every person in the country.

(The author has created all the infographics inspired by the data collected with the help of the World Bank communique)

Copy Editor: Vikash Kumar Upadhyay