The burning issue of ‘Bhu Kanoon’ (Land rights legislation) in Uttarakhand has taken the social media by storm. Every political party in the State is trying to gain political mileage out of this issue. All this comes against the backdrop of upcoming elections, and for now discourse around the same is overshadowed by this particular issue.

The Voices explains the evolution of the roots of the crisis.

HISTORY OF RESISTANCE AND SOCIAL PROTESTS

The historical patterns of protests in the hill State speaks for the origin of current crisis.

During the company and direct British colonial rule, Uttarakhand was categorized as a non-regulated region. After being declared as a scheduled districts zone in 1878,the region was being administered as a backward state and subjected to various exclusive legislations on forest rights and other subjects.

The George William Trail Land settlement of 1822-23 demarcated and documented the boundaries of forest land, farming land and village land for the first time, without infringing the forest rights of local community and allowing them to continue their forest-based subsistence practices.

In 1856 the newly appointed Kumaoun Commissioner Henry Ramsay (1856-1884) introduced revenue oriented commercial forestry. It triggered a series of land acquisitions which were obviously resented by locals as they were highly dependent of forest for a spectrum of daily needs.

Garhwal region witnessed a special form of social protest known as ‘Dhandak’. Herein, locals used to congregate at an appointed spot, often a shrine and demand redressal through the king. Such Dhandkas characterised the Rawain Andolan of 1930 meant to protest restrictions on the customary use of forests.

It is pertinent to mention here that, in terms of land ownership, there was a significant difference between hill state and rest of India in the 18th century. The Zamindari system was absent here and about nine-tenths of all hillmen were estimated to be hissedars (partners) in lands, cultivating proprietors with full ownership rights. The hill cultivators were described by Henry Ramsay as “probably better off than any other peasantry in India”.

Surprisingly, intensity of the protests plummeted in the first decade of 19th century and the hillman was confined in the stereotype of a simple law-abiding man.

But the restrictions imposed on the forests in Kumaoun Region by the British Govt. during 1911-1917 were met with violent and sustained opposition which included incendiary fires in the forests by village communities. The later decades witnessed various rounds of protests such as Coolie Begar Andolan, RawaiAndolan, demand for a separate hill state etc. They were more of a confrontational nature than customary one.

POST INDEPENDENCE AND ADVENT OF CHIPKO

According to experts, the post-independence land rights governance in hilly state inherited colonial policy traits and lacked major attempts of land resettlement barring one during 1960-64.

After the devastating floods of 1970 in Alaknanda River, the village communities started to realize the links between deforestation, landslides and floods. Awareness was intensified by a cooperative organization founded by Chandi Prasad Bhatt namely Dashauli Gram Swarajya Sangh(DGSS). It also called for local employment through Forest Labour Cooperatives (FLC’s) by sustainable use of their forest resources. But the Indian Govt continued to auction the forests around the region and gave felling contracts to private businessmen. The village communities along with the DGSS offered stiff resistance which often yielded results.

On 26th March, 1974 at Reni village in Chamoli a local girl saw the private contractors arriving for felling operations. She rushed to inform women in the village. The head of their Village Mahila Mandal namely Gaura Devi suddenly took charge and mobilized women to oppose forest felling operations. They hugged the trees to protect them. Eventually the contractor’s men were forced to leave and CHIPKO was born.

In response to CHIPKO, the government constituted a forest corporation or Van Nigam to confront all forms of forest exploitation. Initially Nigam allotted forest lots to FLC’s as desired by locals, but later reverted to the old system of forest auctions and allotment.

The Chipko movement in Badhyargarh (1978) was organized to oppose one such act by the Van Nigam. Renowned activist Sunderlal Bahuguna went on a hunger strike and forest officials had to abandon felling of trees.

Above mentioned events confirm that lives of local village communities in hills is inextricably entwined with their social and cultural fabric centered around topographical uniqueness. In order to escape the maze of commercial economy and for their own existence, this land of gods has become a landscape of resistance.

POST STATEHOOD

After the formation of Uttarakhand in 2000, popular calls for a separate land law along the lines of the neighboring state of Himachal Pradesh intensified.

First Chief Minister of H.P, Y S Parmar steered the passage of the H.P. Tenancy and Land Reforms Act 1972 (TLRA), which gives an extra judicial protection to masses from illegal selling and purchasing of village lands. Section 118 of TLRA has not only barred and restricted the transfer/sale of land in the state to the non-agriculturist of the country but also to non-agriculturist of the state itself.

But rather than drafting special land laws in harmony with the ecological nature and sustenance requirements of village economies, the governing brass in Uttarakhand adopted The Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act (UPZALR), 1950.

In 2003, ND Tiwari Govt. introduced an amendment in the act. Now as per section 152 A and 154 of this Act, a person who was not the holder of any immovable property before 12.09.2003 was barred from purchasing property in Uttarakhand except the land under municipal limits with a ceiling limit of500 sq m. However, in exceptional circumstances a person or a company was allowed to purchase land for various commercial purposes but only after the approval of District Collector and Govt.

Later in 2007 the Govt led by B. C Khanduri also amended the act and reduced the ceiling limit to 250 sq m for the outsiders.

Studies have identified that the fraction of cultivated land in Uttarakhand is on a decline due to the absence of proper land settlement policies. As per reports, the land under cultivation in 2020 is 6.4 lac hectares against 7.7 lac hectares in 2008. The avg landholding too has witnessed massive a dip. Most of the land now rests with the Forest Department which has been auctioning it for various purposes allegedly without the participation of local village communities. This has triggered the migration of breadwinners of these village communities.

In addition to this, the situation of land ownership in Dalits of the state is a concerning issue with only 2% of Dalits owing land. Though the UPZALR act has a provision that any surplus or excess land around a village community be granted to landless labourers or Dalits under section 157A, sub section 159 (2) (A), 143(A), 143(B), 143(C), 143(D). Such land transfer can be initiated with the approval of District Collector with the stipulation that the concerned landowner belonging to Scheduled Caste shall have land not less than 1/8 acre which is 63 naali in hills. But the pace of such initiations has been lackluster.

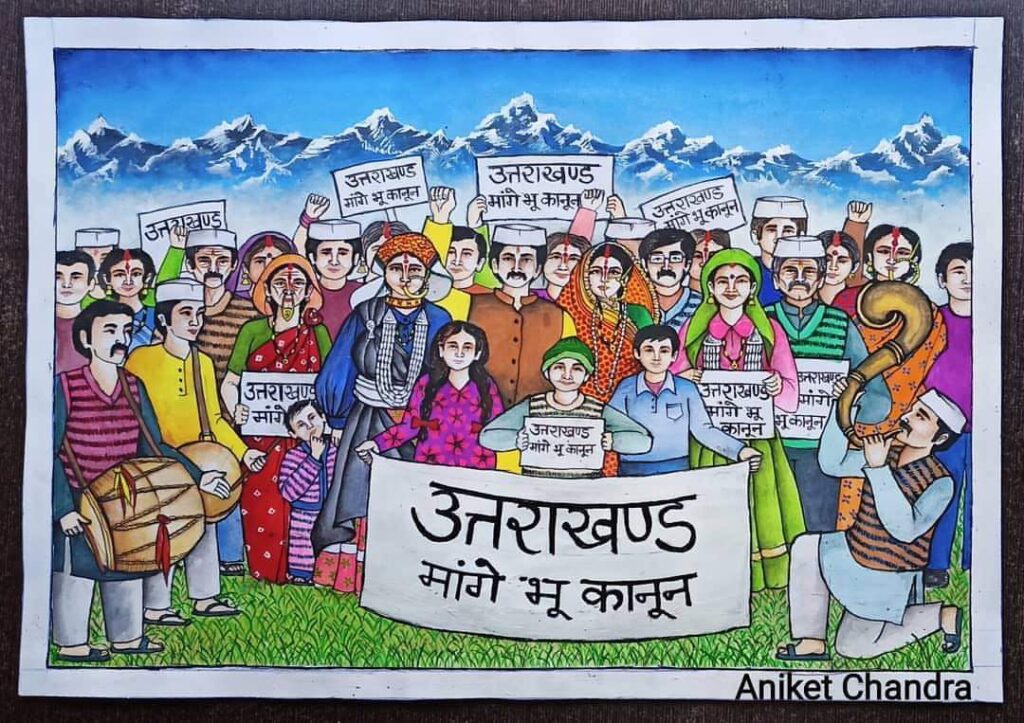

In a debated move, in 2018, current ruling govt amended the land law and completely abolished the ceiling limit under Section 154 sub section(2) on sale of land to outsiders, which triggered the present round of protests. Tawaghat and Kotkhara (2009), Nainisar(Almora) 2016, Naini Danda(Almora) – 2018 were centers of such protests in the past. Activists are demanding exclusive land rights legislation on Himachal’s model.

Experts say that participatory policy making is the need of the hour to balance development aspirations and a sense of traditional belongingness. Creative and constructive engagements will generate opportunities in the hilly terrain and check the migration of locals. Moral and political forces hold the key to check this hilly terrain from becoming another fertile ground for violent dissent.

Story edited by NK Jha