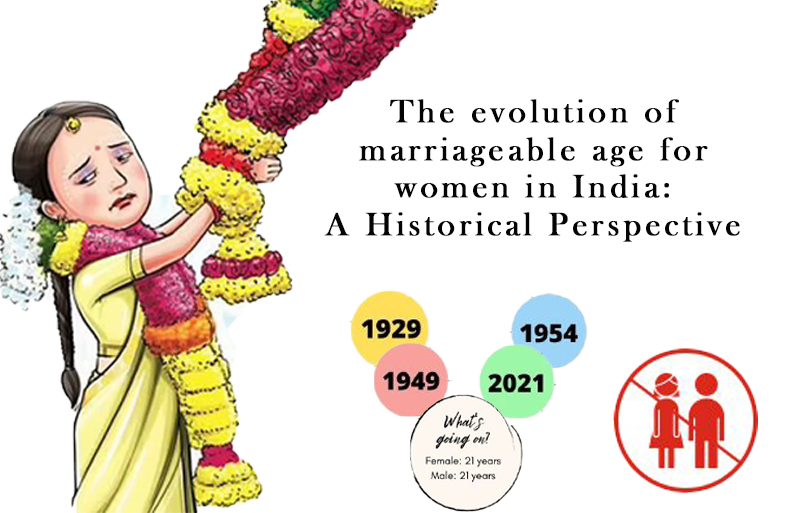

The Union government introduced amendments to the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act on December 21, 2021. The statement of objects and reasons states that the Bill has been brought to address the issues of women in a holistic manner. The Constitution guarantees gender equality as part of the fundamental rights and also guarantees prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of sex. The amendment Bill states that the legal age for women to get married would be raised from 18 years to 21 years. The Bill, hence, proposes to bring women at par with men in terms of marriageable age.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, at least 1.5 million girls below the age of 18 get married each year in India. In June 2020, the Ministry for Women and Child Development set up a task force to look into the correlation between the age of marriage with issues pertaining to women’s nutrition. According to them, the amendments to the Act based on the recommendations of the task force of NITI Aayog will be more effective when facilities like increasing girls’ accessibility to schools and colleges, minimising travel time to educational institutions, enhancing their skill sets, and training them to kickstart businesses comes into practice. The National Family Health Survey report of 2019- 2021 states that 23% of marriages are child marriages in India.

Child marriages compel women to enter the motherhood phase at an early age. Child marriage in India has deep roots in the country’s cultural practices. Hence, it is important to trace the evolution of legislations that legally determined marriageable age in India so that the current amendment Bill may be put in perspective.

In the early 19th century, India was then administered by the British who were only keen to expand their control over companies engaged in military actions. They hardly paid heed to social and economic reforms in India. Therefore, the condition of women was deplorable due to the social, economic, and political uncertainties prevailing in the country. They would remain subservient to their fathers and husbands. There were also minimum occupational choices for women and so, they remained home. After getting married at an early age, they would have to care for their children and run the household.

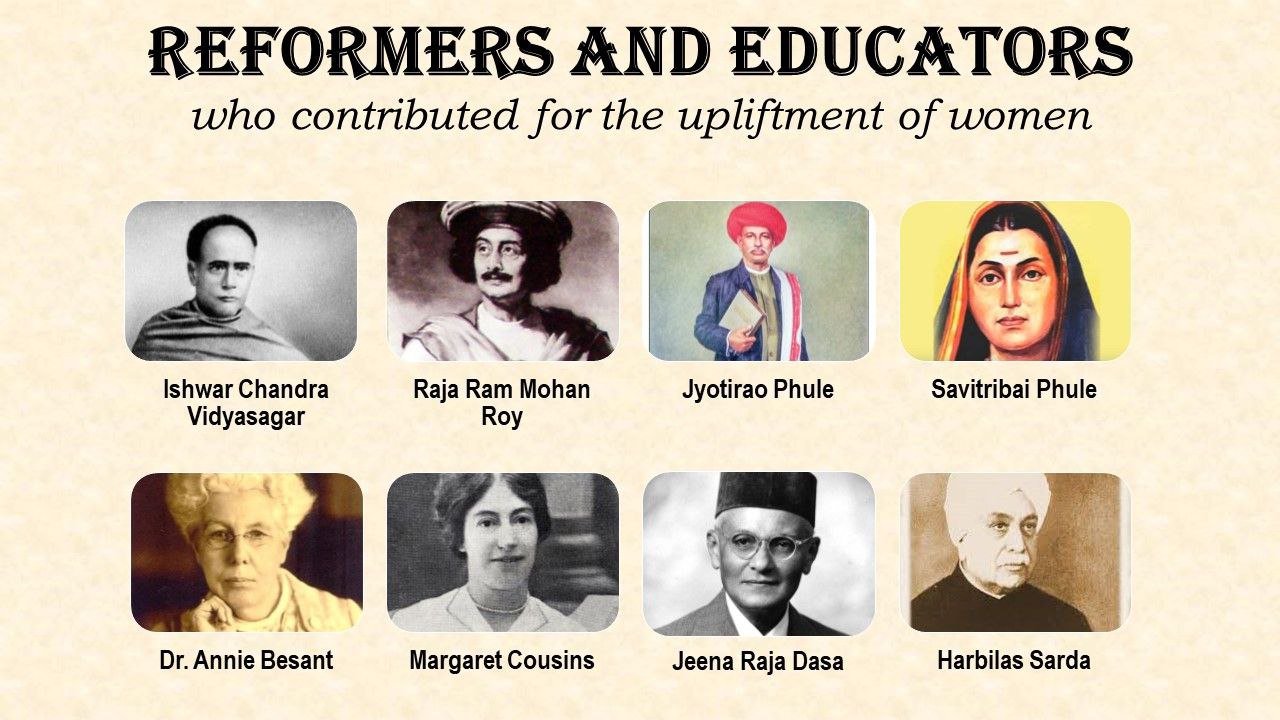

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, an educator and a social reformer of the 19th century from Bengal, was the one who contributed to the removal of the social stigma surrounding widow remarriage and pushed his social reforms agenda that included advocacy against polygamy and education of the girl child. On the other hand, Jyotirao Phule and his wife Savitribai Phule, social reformers from Maharashtra, were the pioneers of women’s education in India. They worked towards the eradication of untouchability, caste system and are also known for their efforts towards educating women and people from the oppressed caste. Dr. Annie Besant, Margaret Cousins, Jeena Raja Dasa were few of those who contributed, in different times, to liberate women from illiteracy, child marriages, the Devadasi system and every other form of oppression. In 1917, Women’s Indian Association (WIA) was founded by Dr. Annie Besant who aimed to raise women related issues. WIA published “Stri Dharma”, a journal that contained WIA’s ideals and beliefs. The journal not only covered socio-economic issues faced by women but also their achievements worldwide. The motto of WIA was to improve educational and social conditions, eliminate early marriages, customs of widowhood and all other impediments to women’s health.

Social reform movements, protests, and rallies took place to draw the attention of the British authorities. When met with indifference from the British rulers, the women approached Indian freedom fighters for support and in 1929, on the advice of Mahatma Gandhi, Harbilas Sarda, a member of the Central Legislative Assembly, introduced a bill to restrain child marriages. After immense pressure, the CLA, where a majority of the members were Indians, passed The Child Marriage Restraint Act. It legalized 14 years and 18 years for women and men, respectively, to get married.

The Government in India passed the law but it did not deliver the desired results as the implementation was poor. This was largely because of the fear of the British authorities who were more interested in expanding their colonial control rather than bringing in social reforms. Gradually, the Hindu and Muslim communities lost interest and the law lacked their support. However, the law stayed active for about three years and did witness a few successful prosecutions. The authorities failed to spread awareness about the Act to rural and marginalised areas of India, especially when the entire country was engulfed in the frenzy of the freedom movement.

The next step for restraining Child Marriages came post-independence. In 1949, The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 was amended and it prescribed the legal age for marriage as 15 years for girls. In 1978, the Act was amended again and the legal age was recognised as 18 years for girls and 21 years for boys. Under this Act, offences were cognizable. Prior to this, actions were taken by the authorities only after a complaint was filed. Years passed but the child marriages still continued in some societies with impunity.

It was not uncommon to hear of girls being sexually exploited, subjected to domestic violence, losing out on education, getting separated from families, facing health disorders, and entering into early motherhood.

In the year 2006, The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act came into existence. It gave the freedom to child brides and grooms to declare their marriage “void” with no divorce. But this freedom laid down conditions. The marriage was voidable only after two years of attaining the marriageable age. Once they cross the time limit, the child marriage cannot be made void. This condition was indeed a loophole of The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act. On the other hand, this Act had provisions for extending support to the victims of child marriages. Under Section 12 of the Act, the child marriage will be automatically void if the lawful guardian or parent is absent at the time of marriage.

The next development happened in 2017. The age of consent for sexual intercourse for girls was 18 years it was not valid for child brides because Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code stated that sex with a girl who is below 18 is rape while laying down an exception, that sexual intercourse by a man with his wife, who is 15 or above, is not rape even if it is without her consent. Independent Thought, a non-governmental organization working for the rights of women and children, filed a writ petition to declare this exception as unconstitutional. With regards to this, Supreme Court judges Justice Madan Lokur and Justice Deepak Gupta recognised marital rape of a girl who is less than 18 years of age as a cognizable crime.

The current amendment Bill has been referred to a Parliamentary Standing Committee for scrutiny after opposition parties protested against it.

Edited By Saptarshi