The tomb of Abdur Rahim Khan-E-Khanan, conserved by Aga Khan Trust, has added new dimensions to its antiquity

Bade badai na kare bade na bole bol,

Rahiman heera kab kahe lakh taka mero mol.

Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khanan

बड़े बड़ाई ना करैं, बड़ो न बोलैं बोल।

रहिमन हीरा कब कहै, लाख टका मेरो मोल॥

The great never praise themselves. When has the diamond said that it is worth lakhs?

A view of Abdur Rahim’s tomb on Mathura Road in Nizamuddin. Photo by Ajay Singh

The above couplet reverberates how the people in history have treated its writer. It’s penned by the 19th-century thinker, poet and Commander-in-Chief of the Mughal army, Abdur Rahim.

Rahim has been a prominent part of growing years in school for many as an easy-to-understand Hindi curriculum in the form of Rahim Ke Dohe. Today, his mausoleum stands tall and is well-conserved in the Nizamuddin East area of New Delhi on Mathura Road. An initiative of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, its extensive conservation has saved this precious monument from getting lost in the oblivion of history. The monument inspires historians like Rana Safvi, who extensively wrote about it in her work ‘The Forgotten Cities of Delhi’.

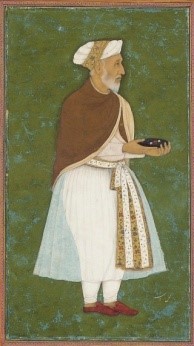

Abdur Rahim Khan-E-Khanan Courtesy Wikipedia

Who was Abdur Rahim?

Named Khan-e-Khanan (King of Kings) by Emperor Akbar, his Commander-in-Chief Abdur Rahim was a famous warrior Bairam Khan’s son. After losing his father at the age of six, young Rahim’s upbringing was taken over by Akbar. Having proven his prowess with the sword as a warrior, Rahim established himself as a litterateur of Bhakta poetry who revered Lord Krishna and other Hindu deities in his dohas and poems. He became one of the nine gems of Akbar’s court. He had also patronised the construction of monumental buildings, canals, tanks and gardens in Agra, Lahore, Delhi and Burhanpur. As the Commander-in-Chief, he led the military expeditions of the Mughals to Sindh, Gujarat, Mewar and Deccan.

A view of the tomb of Abdur Rahim in Nizamuddin. Photo by Ajay Singh

Why is his mausoleum significant?

In 1598 AD, Rahim built a mausoleum for his wife, Mah Banu. It was inspired by the architectural marvel of Humayun’s tomb, which lies just 200 meters from the mausoleum Rahim built. This tomb inspired the construction of the Taj Mahal, and after his death, Rahim was buried near his wife in this mausoleum. Historians say that the structure was mercilessly scavenged for its marble (installed on the dome) in 1753 for the construction of Safdarjung tomb – the last monumental tomb garden of the Mughals. In a way, it has served as a quarry for the grand Safdarjung tomb.

A view of the tomb of Abdur Rahim. Photo by Ajay Singh

How was the tomb restored?

Despite its importance, the tomb of Rahim has long faced neglect in the hands of history. From being plundered and used as a quarry in the 1750s to modern times, when modernisation swallowed up the area around it, the tomb has endured the vagaries of time.

37-year-old Ramakant, a regular visitor to the monument since childhood, says, “In early 2010, this place was scattered with bricks falling apart from the building, on the verge of turning into ruins. Rarely have people visited this place, and the ruins shadowed its beauty.” He adds, “It was only after the monument was restored that one can see historians, YouTubers, travellers, bloggers and nearby area residents now frequenting this place.”

The structure would have been lost into oblivion had the Aga Khan Trust for Culture not taken up its conservation, which began in 2014 and concluded in 2020. Sharing the details over an email interview, Archana Saad Akhtar, Programme Director, Design & Outreach from Aga Khan Trust for Culture, says that despite the immense historical, architectural and archaeological significance of the structure and its prominent location on two of Delhi’s major transport arteries, Rahim’s mausoleum stood in a ruinous condition with a risk of collapse. In 2014, after the completion of conservation works on the Humayun’s Tomb, a World Heritage Site, the interdisciplinary Aga Khan Trust for Culture team — with the support and partnership of InterGlobe Foundation and the Archaeological Survey of India — commenced a six-year conservation effort on Rahim’s tomb.

She adds that following 175,000 man-days of work by master craftsmen, the conservation project is the largest ever undertaken at any monument of national importance in India and the first ever privately undertaken conservation effort under Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

File photo of conservation work done by Aga Khan Trust for Culture on the tomb. Photo courtesy: AKTC

How was the conservation undertaken?

Conservation of the project entailed works done on structural repairs, restoration of ornamentation, façade, dome, landscaping and illumination of the building. Archana adds that the conservation works were spread across the missing patterns, from anastylosis (reconstruction using original architectural elements to the highest degree possible) of the rooftop canopies, restoring the absent stone elements, scientifically cleaning the breathtaking plaster motifs — apart from the structural repairs. Layers of 20th-century paint and soot were removed from ornamentation using soft brushes. Surprisingly, the ornamentation survived the onslaught of time and restored patterns. Voluminous stone blocks weighing around 3,000 kg were also restored. Today, the structure stands conserved, reflecting the glory of the Mughal era.

Historian Rana Safvi

Is Rahim’s legacy getting its due?

In an email interview, historian Safvi says that the Aga Khan Trust for Culture has done a commendable job conserving the monument. “Already the monuments in Burhanpur (in Madhya Pradesh) built by Rahim are on the verge of extinction,” she adds.

Rahim has been governor of Burhanpur and ruled over the area for 37 years. He built the hammam (bath), serai (inn), masjid, and many such places, which are now in decline. She adds that this generation must do significantly more to compensate for the past neglect.

Copyeditor: Vibhuti Landge