Earlier this year, when Sunil Chhetri announced his return from retirement at age 40, the news was not met with celebration but an uncomfortable truth: Indian football had run out of options.

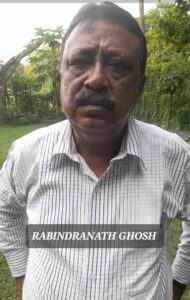

Commenting on Chhetri’s comeback, Rabindranath Ghosh, a former assistant secretary of the Indian Football Association in West Bengal, said Chhetri’s comeback represented something more troubling than just a shortage of talent. “It shows how quickly the supply line for Indian football is drying up,” he stated.

The numbers tell a drastically different story. The world’s most populous nation and largest democracy, India, currently ranks 142nd as per the November 2025 FIFA rankings, a significant drop from its rank seven years ago.

In September 2018, India held the 97th position, just behind Uzbekistan and ahead of Jordan. Today, both those nations will participate in the 2026 World Cup, while India will watch from the sidelines.

This contrast is even more evident when we turn the pages of history. From 1951 to 1970, India continued to excel in Asian football, winning gold at the 1951 and 1962 Asian Games and taking bronze in 1970. The team also finished fourth at the Melbourne Olympics. Indian football experienced a period of dominance in Asia during its golden two decades.

What has happened in the past fifty years remains a question that troubles players, coaches, and administrators.

The Collapse of a Pipeline

Ghosh, Former Asst. The Secretary of the Indian Football Association (IFA) in West Bengal, who has managed the Bengal football team on several occasions, attributes the decline to changes in Indian society. “The Santosh Trophy used to be the major national tournament where the best players were spotted for the Indian football team trials,” he explained. “Now, it has lost all its appeal.”

The economic changes of the 1990s helped turn India into a global power, but also weakened the country’s talent pipeline in football. As the government sector shrank, so did the recruitment under sports quotas, a vital path for talented players from humble backgrounds to land stable jobs while pursuing their sport.

“There is a lack of motivation among young footballers,” Ghosh observed. “With the economy opening up and the government sector shrinking, it’s tougher for talented players to get jobs.”

The problem has worsened due to the limited international exposure. Names of players such as Bhaichung Bhutia and Chhetri, who have proven their mettle internationally, come across as exceptions from a system that has been failing to produce consistent talent.

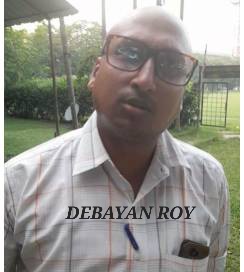

Former national-level player and FIFA-licensed coach Debayan Roy affirms that the nurturing conditions for players have deteriorated, agreeing that the infrastructure for developing young talent has declined. “We need a comprehensive approach that focuses on developing young players and organising national and international tournaments,” he said.

Comparisons and Caution

Pointing at India’s comeback in hockey, with bronze medals at consecutive Olympics after a decade of decline in the 1990s, Roy suggests it as a potential model. However, others caution against making direct comparisons.

Shayne Dias, an associate senior producer at Sports Today, describes the hockey analogy as “an apples and oranges situation.” He suggests that India has always had a strong talent pool in hockey. “The same cannot be said for football, where even our best players are far behind those from other countries.”

Hockey’s lower profile compared to football’s global popularity also made its comeback easier, Dias added. “Hockey isn’t as popular as football, so recovering in that sport was always going to be simpler.”

For Indian football, the challenges run much deeper.

Grassroots or Nothing

All three experts agree on one important point: India’s national team will only improve when the foundation changes. “India’s poor performance stems from a lack of focus on grassroots development,” Dias said. “The national team will only get better when club culture and grassroots football strengthen.”

Ghosh sees promise in projects like the Zinc Football Academy in Rajasthan, which was created to nurture young talent using scientific training methods. “Identifying and developing young talent scientifically is urgently needed,” he remarked.

Proposing a short-term solution, Dias suggests allowing Overseas Citizens of India and Players of Indian Origin to be the representatives of the country. This could result in providing an immediate boost while longer-term changes take effect at their own pace.

However, he remains realistic about the scale of the task ahead. “The talent pipeline for Indian football is already dry, especially for strikers and goal scorers,” he stated. “To change this, we need long-term planning and to coach children from a young age.”

Roy stresses that success will need cooperation from various sectors. “Corporate partners and the government need to unite to make this effort work,” he said.

What about 2030?

Millions of Indian football fans across the country hold on to a familiar dream: seeing their team compete on the biggest stage in the 2030 World Cup. The question has now shifted from whether India can reclaim its earlier dominance in Asian football to whether it can establish the necessary systems to compete effectively.

The distant journey from rank 142 to one of relevance will require more than just talent. It will need a strong commitment from institutions, financial investment, and a willingness to plan not just for election cycles but for generations.

For now, the clock is ticking and the time is running out for Indian football.

Copy edited by: Shiekh Mishal